Dalagang Bukid: The Mountain Maiden of the Seas (DGF Award Winner)

I met the mountain maiden of the seas when I was 20 years old. I was in Capiz the summer after Typhoon Yolanda, volunteering alongside a handful of other bright-eyed and useless foreigners. My assignment was to write a cookbook of local recipes that my NGO could use to raise awareness of the plight of Capiz. A tangential task, but I took it as seriously as a college sophomore could, studying the intricacies of Capizeno cuisine like a new language.

This involved a lot of pointing and asking "Ano na?", repeating the answers like an American echo. I asked the vendor to name all the creatures in his bike-bound cooler. The plump ones, just fat enough to fill a dinner plate, striped like sailor's shirts: bugaong. Speckled with full, pouting lips: alatan. Pale and slender, shimmering pink around the edges as if with a dusting of rouge: dalagang bukid.

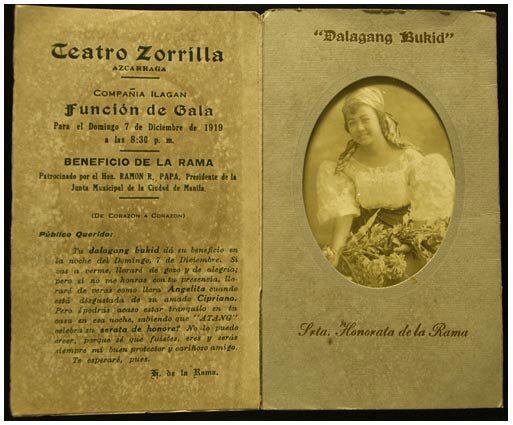

Here were two words I knew. Dalagang bukid can translate as "country maiden," a folksy phrase that often appears in old kundiman love songs. The fish shares its name with the first Filipino feature film (released 1919 and now lost), in which the titular dalaga is a downtrodden flower vendor. In Capiznon and other Hiligaynon languages, bukid tends to have less tame connotations ― not the familiar world of rice paddies and bahay kubo but the mountains, still a realm of mysticism and possible danger in the lowland imagination. But for the Panay Bukidnon, an indigenous people who call themselves the Tumandok or Suludnon, the bukid is home.

I met several members of the Panay Bukidnon that summer, when many highlanders descended to the lowlands for aid. Fiercely proud of their culture, which was protected through the ravages of colonialism by the isolating mountains, they still wear their scarlet-red traditional clothing to mark the rituals that punctuate their lives. Locals told me that the red-tinged dalagang bukid is named in reference to these mountain dwellers' clothing. However, Bukidnon men and women both wear red; why dalaga?

Clues can be found in the epic ballads of the Bukidnon, which chronicle the precolonial heroes and deities of the Visayas, as well as in the ballads' tellers. Historically, the greatest repository of ballads were the binukot — a mythologized class of maiden who I posit as the namesake of the dalagang bukid fish. The ballads these maidens passed down often include binukot characters, described as paragons of beauty with hair that flows to the ground, legs as smooth as banana trunks and skin white as balanak, another kind of fish.

The tradition of raising girls as binukot, Hilgaynon for "secluded," has joined the annals of outdated methods for controlling women's lives and bodies. After the age of three or four, noble families cloistered their daughters indoors to protect them from the sun and male eyes, thereby bringing up their value on the marriage market. Forbidden from engaging in manual labor, the binukot spent her days practicing needlework and memorizing ballads. At 13 or 14, she was married off for the highest brideprice like a carefully-raised prize hog.

Once practiced throughout the Visayas, the practice of cloistering girls petered out in the colonial period, holding on longest among the isolated Panay Bukidnon. (The last known Bukidnon woman raised this way, Rosita Caballero, died in 2017.) Over time, the pale, sheltered binukot became associated with the mountains where the tradition remained, romanticized by lowlanders and conflated with the dalagang pilipina, a Spanish-inflected feminine ideal that involved a similar preoccupation with chastity. Hence, the binukot became known as the dalagang bukid.

A common trope in Greek mythology has the hero transform into a constellation after his death, a permanent record of his tale. In the Filipino epics, whose gaze points more often to the seas than to the skies, transforming into a fish may be the closest equivalent. The binukot is gone, but the dalagang bukid fish remains, a mnemonic for her myth. Their red bellies flash through the reefs and shallows like a shadow of the binukot's red skirts.

In Capiz, I served the dalagang bukid simply, fried in the charcoal-fired "dirty kitchen" with a side of ensaladang ampalaya. I've had it rarely since; Caesio cuning is hard to find outside of Southeast Asia, and I've spent the past five years traveling far afield. But I think of her often.

Though born in the US, I have roots in the Visayas, and if I was born there a millennium ago I may have been kept in my room all my life. Instead, I can move so far and so fast that I reached the place of my roots, like the dalagang bukid fish, flitting through the Southeast Asian seas as fast as it can but always returning home.

This article won third place in the 2020 edition of the Doreen Gamboa Fernandez Food Writing Award. It appears on the Doreen Gamboa Fernandez Food Writing Award website, in Positively Filipino magazine, and on ANCX.ph, the online lifestyle magazine of ABS-CBN.

Add a comment

0 Comments Add a Comment?