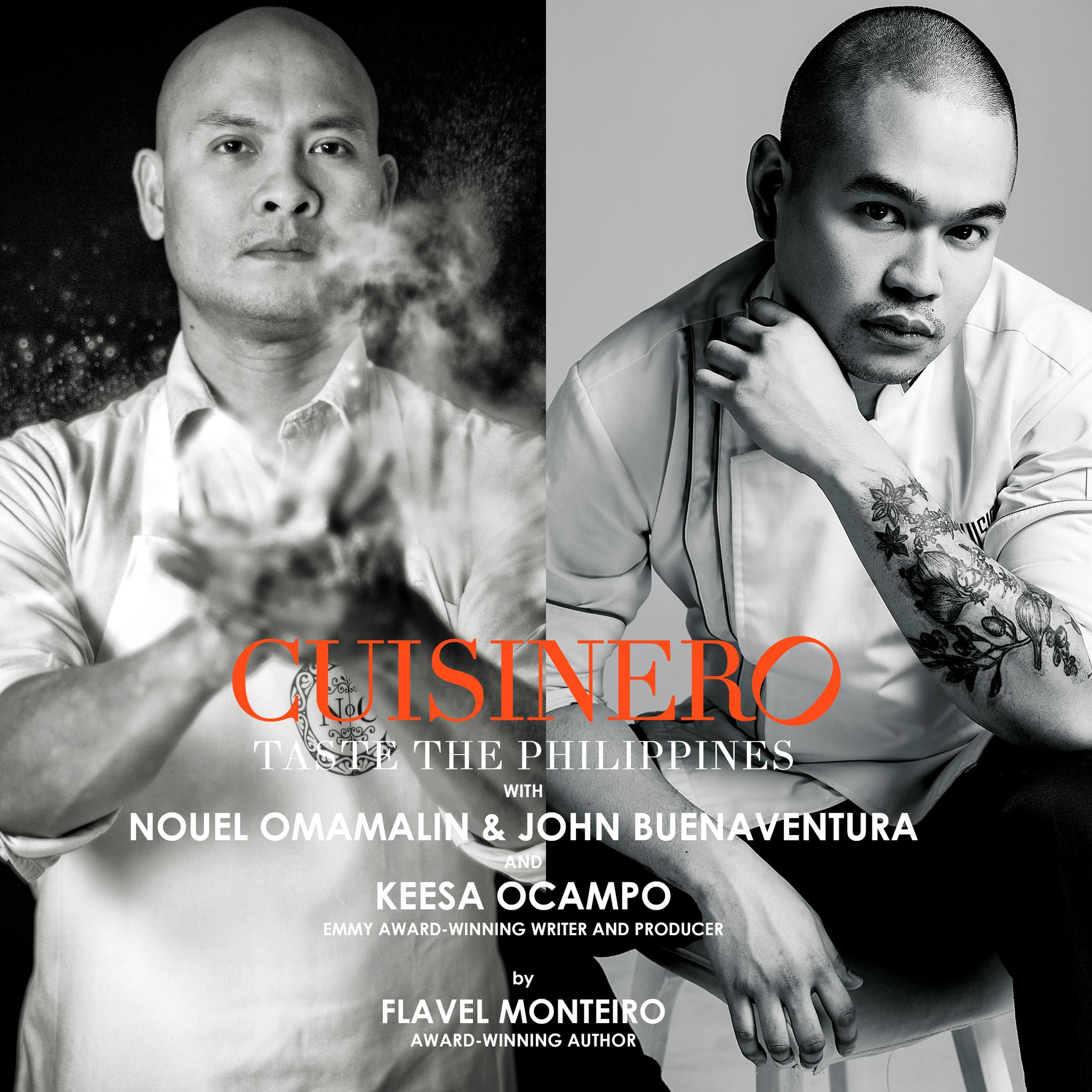

"Cuisinero: Taste the Philippines"

Like the lightning fires currently tearing across California, the coronavirus crisis sparked a complex of many smaller crises, food issues prominent among them. First, there were the runs on supermarkets for those who could afford it, and empty shelves for those who couldn't. Then restaurants found themselves in freefall as governments ordered the shutdown of dine-in service. Millions of people, including many in the food industry, have lost their jobs. More than ever before are relying on nutritional assistance programs.

But food has also been a comfort, one of the few pleasures left to people sheltering at home. Early on, home cooks rediscovered the simple satisfaction of kitchen projects, of slow processes that they could control — sourdough, pickles, long-simmering stews — and of feeding others. Chefs joined in, returning to their shuttered restaurants to make meals for frontline workers and vulnerable people. Many later gave up some of their sales to support the social justice causes that took the spotlight in late May.

"Cuisinero: Taste the Philippines" is a cookbook for this moment. The e-book was published online Aug. 15 to benefit Filipino restaurants in the United States through the Filipino Food Movement and underprivileged children in Mindanao through Philippine International Aid, and has received two mentions on the Gourmand World Cookbook Awards Summer 2020 list. It is a multi-layered collaboration that reflects both the pleasure and the pain of cooking in the pandemic.

Co-authored by food writer Flavel Monteiro and ABS-CBN director and writer Keesa Ocampo, "Cuisinero" features recipes from two leading Filipino chefs of the Gulf region, John Buenaventura and Nouel Omamalin. (Full disclosure: I worked with Keesa on the planning committee for the Filipino Food Movement's Savor Filipino Summit.) The book opens with no less than half a dozen forewords by chefs, food writers and diplomats and closes with afterwords from Mona Lisa Yuchengco (founder and publisher of Positively Filipino) and Sonia Delen (president of the Filipino Food Movement), all musing on the effects of the pandemic on everyone from five-star restaurateurs in Dubai to children in Davao.

Between those timely forewords and afterwords are over 200 pages of culinary escapism. Even the structure feels escapist; while most multi-course cookbooks leave the desserts for last, "Cuisinero" starts with five chapters of chocolates, cakes, kakanin (rice cakes) and other sweets by Nouel Omamalin. Then comes a menu plan for a "Fiesta Filipina" — presumably one for the future, as large gatherings are still discouraged in most parts of the world — with recipes by the co-authors, followed by three savory chapters by John Buenaventura.

Many of the recipes, especially as they're plated in the full-page photographs, require the tools and ingredients available to professional chefs — not many home cooks have gold leaf lying around to garnish chocolate-coated biko (sticky rice cake), for example. But just as many are manageable takes on dishes familiar to Filipino kitchens, cheffed up enough to feel special.

Edible flowers and caviar garnishes notwithstanding, Buenaventura's recipes are all solid Filipino classics, with the addition of the occasional European technique. His ginisang ampalaya at itlog (stir-fried bitter melon with egg) recipe, made with a French-style soft scramble, is the kind of subtle masterpiece that I imagine a Filipino chef making after a long dinner service in a five-star kitchen. And I could eat Buenaventura's Thai chili sofrito, part of his cheesesteak-inspired lengua salpicao recipe, on anything (including that soft scramble).

Omamalin's recipes are more technique-heavy, but the photographs are beautiful enough to make an indifferent home patissier want to try their hand at chocolate flocage or smoke-scented pavlova. A few recipes are easy enough for beginners: I plan to make Omamalin's chocolate chip cookies, doctored with finely ground cafe barako (a.k.a. cafe liberica), my standard. The cornstarch and cold butter in the dough yield a thick, soft cookie, chewy in the center if you let them cool to room temperature and molten if you can't wait.

Omamalin says his favorite recipes in the book are his takes on biko, both because biko "brings back so many memories" and because it got him to the semifinals at the 2018 Valrhona Chocolate Chef Competition in France. Biko also happens to be one of my favorite Filipino sweets — it's the only kakanin my lola taught me to make before she moved back to the Philippines — so I tried one of Omamalin's recipes. To a standard coconut-based biko, he adds a liberal amount of Valrhona Dulcey, a "blond" chocolate made by caramelizing white. The result, topped with Luzon-style latik (coconut curds) just like my lola used to make, is both novel and familiar, luxurious and comforting — just the kind of thing we all need right now.

"Cuisinero: Taste the Philippines," published by WG Magazines, $4.99 for the digital book donated to the Filipino Food Movement and Philippine International Aid, filipinofoodmovement.org. A limited print run is under discussion.

A version of this article appeared in Positively Filipino magazine.

Add a comment

0 Comments Add a Comment?